|

I was fortunate to have some outstanding teachers in high school, Mr.

Barrett in math, Miss Simmons in English and Mr. Power in chemistry and

physics. Miss Simmons believed in reincarnation, and she further

believed that she was Cleopatra reincarnated. This was not a secret, as

she would proclaim it from time to time. She didn't use a text book for

grammar. She developed her own mimeographed course, which she called,

"Grammar with a Hammer". A little strange, but an excellent teacher.

Mr. Power was also an excellent teacher, but was on a temporary

teaching permit because he couldn't pass the licensing exams. He was a

very nice guy, and could explain what he knew, but had difficulty

learning new stuff. This was particularly noticeable after the atom

bombs were dropped on Japan in 1945. I was in his chemistry class and he

and the class had to learn about atomic energy at the same time.

In

one assembly program during my junior year, teachers decided to have a

quiz program of juniors against senior. I think Miss Simmons was the

instigator because she did not teach seniors, and would talk on and on

about her "brain trust". There were 8 juniors on a team against the

team of 8 seniors. Pete Poletti asked the questions. About

halfway through the match, he turned to the juniors and said, "I'll

give you 5 seconds to divide 75 by a half." I raised my hand and

shouted 150. Pete said that I was wrong. I sat there trying to figure

out what he meant when I noticed Mr. Barrett, all 6'6" of him,

unfolding himself from his seat and saying, "Pete, he's right." Each

correct answer was worth 5 points. I scored 95 out of the 190 the

juniors' total. The seniors had 225.

|

1947

|

Weldon

E. Howitt was the principal of the high school for as long as anyone

could remember, but had retired about 1944. At graduation, he gave a

$25 prize for "Advanced Physical Science". Until my senior year, it had

been given to the senior who received the highest mark on the physics

regents exam. I got 100% on my physics regents. That year, the prize

was given to the senior who had the highest regents average in

chemistry and physics. I scored only a 96 on the chemistry regents, but

Kuno Schwartz had a 98 in chemistry and a 99 in physics, so he won the

prize. Two years later, when Lee had the highest average, and

the

highest physics regents mark, the prize was given to a girl who took

chemistry in her senior year, instead of physics, and scored higher on

that regents than Lee did on physics.

When the district built a new school, it was named after Mr. Howitt. |

|

June 1947 |

I graduated. It was

assumed that I would go to college - I was a great student with

wonderful marks, my overall high school regents average was above 95%,

so how could I not go to college? But I did not want to go. I didn't

know what I wanted to do, but I did know that I didn't want college.

The idea of going to college wasn't scary, it was repellent, and I

don't know why. I was never able to even broach the subject with my

parents, so I went to the University of Michigan engineering school.

I was not interested in

engineering, but it was felt that that was where I belonged and I could

not refuse. For whatever reason, I was not housed on campus with the

freshman. I was 7 miles away in Ypsilanti in old army barracks with

upper classmen, with a U of M bus as the only transportation between

the two. It was a very unhappy situation and I did badly. In the second

semester, I moved on campus, but I had no interest in the work and I

did poorly. I never went back and I have never regretted not having a

college degree, but I'm sure that my parents were greatly disappointed.

|

1947 |

|

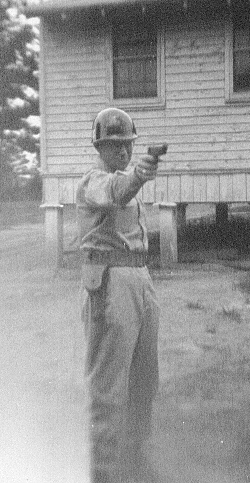

November 1948

Ah! The warrior and the movie star.

After my one disastrous year at

the University of Michigan, I enlisted in the army because, for one

year only, the army allowed 18 year-olds to enlist for one year and

were then exempted from the draft. |

Congress liked the one-year enlistment idea,

it was

theirs, but the army hated it. They had no programs for us and didn't

know what to do with us. The army wasn't permitted to send us overseas,

and there was nothing for us to do in peacetime in the U.S. The result

was that in my 52 weeks in the army, I went through the 8 week basic

training course 5 times. I also had 4 weeks of leadership school, a

month's worth of furloughs, and the rest of the time was just wasted.

Towards the end of my enlistment, I was assigned to the Engineering

Corps, where I learned how to use a gin pole, with and without a dead

man. I also learned how to put together a ponton bridge, but we 18 year

olds were not allowed to touch the equipment. We did learn how to chop

grass with sharpened sticks because we engineers didn't have

lawnmowers. It wasn't a bad way to spend a year, and I did enjoy the

close order drills, especially when I was the acting drill sergeant.

There were some fun times.

One of the first things

that happened after induction into the army was the taking of the Army

General Classification Test (AGCT). This was 2 three hour sessions of

multiple choice tests. Dad had a friend who was a research psychologist

at NYU. He had needed volunteers to take tests he was devising, so dad

volunteered Lee and me. From about 1944 to 46, we would go to NYU to

take tests, so I learned how to take them and how they were scored. The

AGCT was just another test to me. I listened very carefully to the

directions, and when the emphasis was on answering every question,

whether you knew the answer or not, I knew how the test would be

scored. The machine would record only incorrect answers. So, I answered

only questions when I was reasonably sure that I knew the answer. My

score was 796 out of a possible 800, which actually meant that, of the

questions I answered, I got 4 wrong.

|

|

|

The AGCT score was part of my permanent record and got

me some respect

from the non-commissioned and commissioned officers, who kept trying to

get me to sign up for officer's candidate school. I think it was also

responsible for the 3 promotions that I got in the one year.

Every soldier gets a copy of the army field manual, which is an

instruction book on how to be a soldier and the rules and regulation. I

actually read it, so I knew, at least in theory, how things were

supposed to work. So, for instance, when the platoon is standing at

attention, rifles on shoulders, and the drill sergeant orders, "Right

Face", I knew that was an illegal command, because the field manual

says that you cannot give a facing command when rifles are on

shoulders, and would therefore holler, "As you were." thereby

countermanding the order. This happened so frequently with one drill

sergeant that he started asking me which commands he could give.

|

|

I had received a furlough

in April 1949 to go home for Easter/Passover. The train left Columbus,

Georgia very late at night, and by the time I got there, it was

crowded. I got onto the first car of the 3 car train and started

pushing my way back. The second car seemed just as crowded. I kept

pushing, and miraculously, the back of the car was fairly empty. I

walked into the last car and found lots of empty seats, so I laid down

in one and went to sleep. I was awakened some time later by 2

conductors. The white one shook me awake, while the black one

just stood there. The white one told me that I would have to move to

the front of the train since the back was reserved for blacks. Came the

dawn! It was then I realized why there were so many empty seats. He

pointed to a sign which said that rule 48 of the Georgia Public Service

Commission reserves the back for blacks. I told him that since we were

going to Washington, that made it an interstate trip, the Interstate

Commerce Commission had no such stupid rule, and I refused to move.

They went away and I went back to sleep. We were near Washington when I

woke, the car was full of white people and the train was 8

cars long. Apparently, when they added cars, they made the blacks move

back.

One summer day, at Fort

Benning, Georgia, our platoon was out in the

field using sharpened sticks to cut grass, when a runner arrived with

orders for me to get into my Class A uniform and report to a lieutenant

in a company classroom. I rushed back to the company area, showered,

changed and reported to the lieutenant. He asked

me the speed of

light, I told him, he thanked me and told me to go back to whatever I

was doing before.

In late September, 1949, about three weeks before I was to be

discharged, I was put up for promotion and was told to report to the

battalion commander, a major I didn't know. This was to be my

interview for the promotion. He started by questioning me on

engineering topics - gin poles, trenching equipment, bridges, etc. I

wasn't able to answer all of his questions. Then he asked if

I knew the binomial expansion theorem and the quadratic formula. I told

him I did. He asked me to explain them since he was going to take a

test for a promotion and he just couldn't understand them. We worked

on them for a while until he got them. He then told me that he was

going to approve my promotion, not because I knew anything of benefit

to the army, but because I was a good boy. |

|

|

|